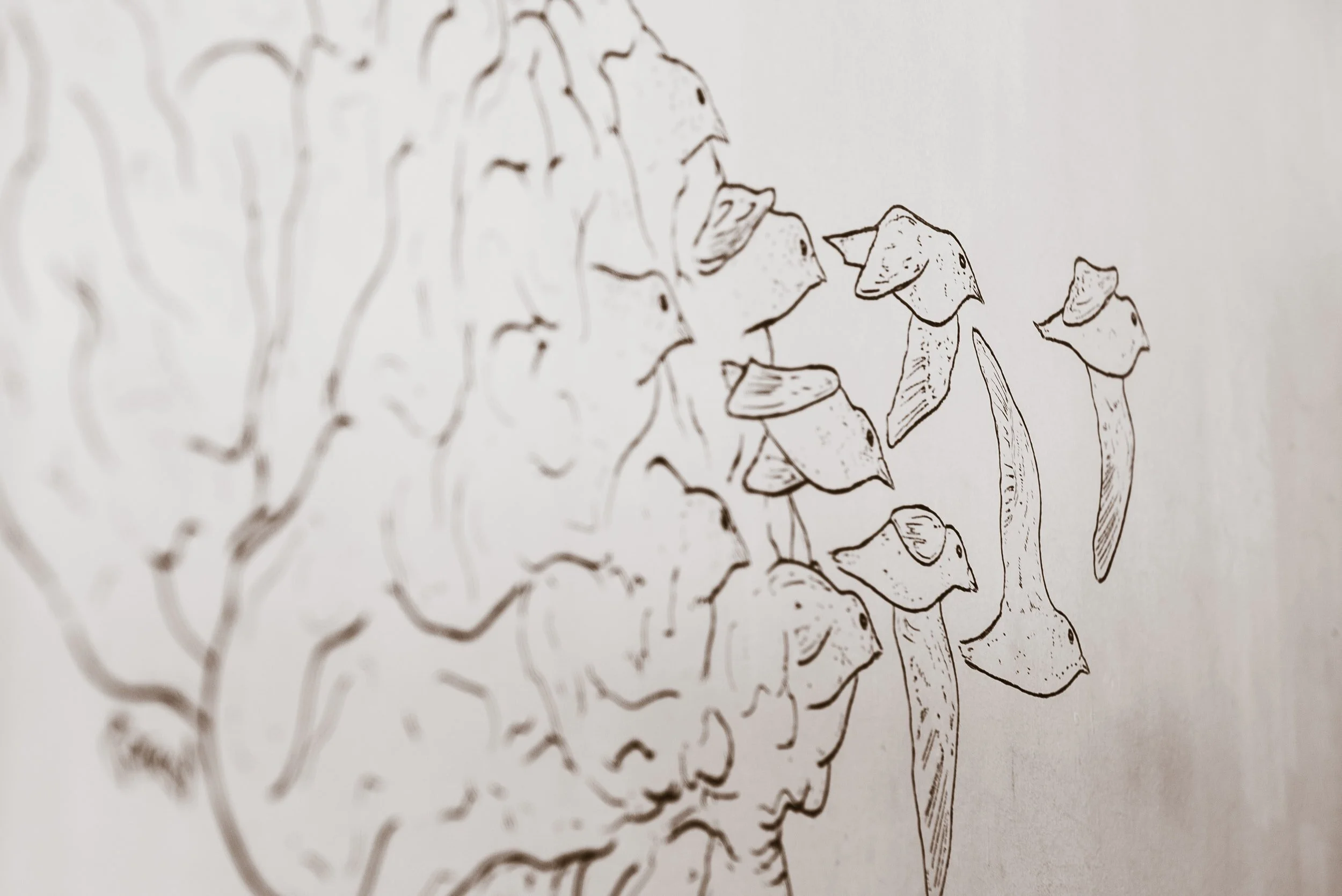

Our brain is our context tool, the biochemical and electrical machine that makes sense of our surroundings and integrates our behavior with that of other members of our species, mingling our past and current experiences into a state of being that we perceive as consciousness, as self.

The feeling of self includes the constant flow of sensorial inputs, which are run through our brains’ relevance filters and integrated with a stream of thoughts and emotions. Sometimes this stream transports happy feelings. Too often though, nagging worries drift along, and can accelerate into the unruly currents of anxiety and depression.

Some people have experienced a state that goes beyond the feeling of self – a so-called mystical experience of boundless and oneness, which can occur in nature, through meditation or religious ritual.

As spiritual as those mystical states might feel to the individual, they are – naturally - part of the brain biochemistry too.

The intersection of the feeling of self and the perceived mystical self-loss-experience is exemplified by the action of Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and other psychedelic drugs.

“When you study natural science and the miracles of creation, if you don't turn into a mystic you are not a natural scientist.” Albert Hofmann once said.

The Suisse chemist worked at Sandoz Laboratories (now Novartis), where he synthesized a substance called LSD in 1938. Finding no immediate use for his discovery he let it rest for a couple of years before revisiting it in 1943, after he’d experienced a “peculiar presentiment”.

The ball began rolling, when he accidently ingested a bit of the substance, which led to what he described as a “not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination”.

Intrigued he consumed what he considered the smallest active (in reality quite decent dose) of 250 micrograms of LSD. What followed was a memorable bicycle trip that Hofmann took from the lab to his home. While at first, he was terrified and paranoid those feelings gave way to enjoyment of what he was experiencing. “Little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes.”

On that day, Hofmann discovered LSD was a psychedelic substance. It changed him forever.

He would later say:

“LSD is just a tool to turn us into what we’re supposed to be.”

He wasn’t the first to see this potential in psychedelics - for centuries, different native cultures had used substances such as “magic” mushrooms, mescaline or ayahuasca as tools in religious rituals, to enhance spirituality.

Invigorated by his bicycle-trip, Hofmann hoped that his new discovery would find uses for treatment of psychiatric patients. The idea was picked up quickly and a number of psychiatrists investigated the effects of LSD in psychiatric patients, many reporting benefits, but few living up to scientific standards that would make the results interpretable today.

While LSD flooded the Hippie movement and broadened (or at least altered) the consciousness of the flower-power generation, the drug didn’t find the accepted medical use as Hofmann had hoped for.

Meanwhile, the supposed transformative qualities of LSD spawned new lines of experimentation which contributed to the drug’s notoriety. From slipping LSD to ignorant subjects in the CIA’s MK Ultra program (which was supposed to defend against communistic mind-control techniques), to NASA-founded experiment of interspecies (as preparation for extraterrestrial) communication. In the latter John Lilly (himself a fond LSD user) tried to communicate with dolphins and injected LSD into the animals – which luckily didn’t do any harm to them but also didn’t make them speak English. There is some more beef to the dolphin story that goes from absurd to sad, but that’s for another time…

When the summer of love came to an end, the idea that psychedelics where a means to cure mental illness and gain a higher state of reality, be it in psychotherapy or in a recreational setting, was dwindling. As another Hof(f)man(n) said - this time part time revolutionary Abbie Hoffman:

“The 60’s are gone, dope will never be as cheap, sex never as free, and the rock and roll never as great.”

At the end of the 1960s, the Drug Enforcement Administration classified LSD a controlled substance. Other psychedelics followed the same fate. Hofmann’s miracle drug had turned into his “problem child.”

Psychedelics lurked in the shadows for decades, not bothering many people except for recreational users and a few dedicated scientists, artists and drug policy reformers who hadn’t quite given up on the idea that psychedelics could hold benefit for humankind.

In recent years though, the concept of using psychedelics for treating patients with mental illness is slowly rejuvenated and starts reaching the mainstream media. A few reports showed that psychoactive and psychedelic drugs helped patients with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric diseases when combined with talk therapy. Those studies go beyond the mountain of anecdotal evidence accumulated in the 1950s and 60s.

Does this mean we should all take LSD and we will live happily ever after? Likely not. There appear to be severe psychological risks to psychedelics and a bad trip might be just as transformative (in a negative way) as a good one. But maybe there is a chance to exploit the substances in a controlled setting for treatment of psychiatric diseases, and – who knows – for personal enlightenment.

First, though, we will have to gain a better understanding what LSD and other psychedelics do to the brain.

Tune in next Thursday for a discussion of recent results of bioimaging and behavioral studies, which try to decipher the complex action of psychedelics on the neurobiology of our brains.

Until then I leave you with another saying from Albert Hoffman, who died in 2008, witnessing only the beginnings of the recent upsurge in psychedelics research:

“I go back to where I came from, to where I was before I was born, that’s all.”